Greta Garbo

The Legendary Star's Secret Garden in New York

TEXT BY GRAY HORAN

|

FRITZ VON DER SCHULENBURG / © GRAY REISFIELD

|

Greta Garbo, who created memorable roles in Anna Christie, Anna Karenina and Ninotchka, found refuge from the intrusions of an avid public in a New York apartment near the East River from 1953 to her death in 1990.

|

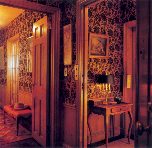

A carpet Garbo designed lines a hall, when a painting by her brother, Sven Gustafson, hangs above a Louis XV banquette. In the elevator vestibule at right is a circa 1700 British School oil.

|

FRITZ VON DER SCHULENBURG / © GRAY REISFIELD

FRITZ VON DER SCHULENBURG / © GRAY REISFIELD |

DAVID HAYS / © GRAY REISFIELD

DAVID HAYS / © GRAY REISFIELD |

A detail of paneling in the bedroom, where Garbo took panels from a Swedish armoire to from a bed and a niche.

|

“THERE WILL NEVER be another Garbo.” She said it herself in her own confident, charming manner. She was responding to a magazine article I had shown her about a new actress who was touted as “the next Garbo.” “No, there will never be another Garbo,” she continued. “I'm different inside.” The emphasis was on the last word.

What was she like inside? So few people really knew. Both on- and off-screen, Greta Garbo evoked a sense of wonder. She created some of the screen's great characters in movies of the same name: Queen Christina (1933), Anna Karenina (1935), Camille (1936), Ninotchka (1939)–all were provocative and timeless. About herself, she left the public guessing. She was determined to live privately.

This was difficult for Garbo. Her beauty and mesmerizing film performances and catapulted her to fame at the cusp of womanhood. She was only seventeen when she starred in Mauritz Stiller's Gösta Berling's Saga (1924). With her unparalleled success came the less desirable trappings of stardom. She was pursued through out her life by persistent fans, reporters and photographers. She rebelled at the intrusions, wishing desperately to be left alone.

|

Garbo being filmed in 1929 by cinematographer William Daniels for her last silent movie, The Kiss. “You get a face like that before a camera once in a century,” observed director Mauritz Stiller, who brought then-19-year-old Greta Gustafson to the United States in 1925. A tree-time Oscar nominee, Garbo was given a special 1954 Academy Award for her “unforgettable screen performances.”

|

TURNER ENTERTAINMENT CO. / MGM COLLECTION /

COURTESY GRAY REISFIELD

|

“I was on the lam,” Garbo said (she frequently peppered her speech with such colloquialisms), recalling the Hollywood days when she rented or owned a series of houses, constantly moving to elude inquisitive neighbors and relentless voyeurs. When preparing for a role, she was serious and concentrated; she would take her tape recorder to her bedroom and work for hours on end. It left her little time for homemaking. In fact, she acquired relatively few possessions for her home during this period in her life–notably a coveted seventeenth-century Swedish country table that belonged to her beloved film director, Mauritz Stiller, a bedroom set and a plethora of books on art and history. Of her Spartan surroundings Garbo would explain,” I worked. When was I going to sit in the living room?”

|

FRITZ VON DER SCHULENBURG / © GRAY REISFIELD

FRITZ VON DER SCHULENBURG / © GRAY REISFIELD |

Renoir's 1909 Léontine et Coco, which depicts the artist's son Claude, is displayed in the living room. Garbo had a passion for art and antiques and began collecting works by Renoir in the 1940s. Louis XV fauteuils attributed to Jean-Baptiste Tilliard flank the fireplace, where late-18th-century famille rose roosters are set alongside 19th-century Chinese porcelain boxes. The taboret is Louis XVI.

|

Residential Los Angeles offered an unprotected lifestyle. One night the actress found herself dangling from the drainpipe outside of her bedroom window, waiting for the prowler inside to finish prowling. She needed security. It was time to move to New York, which offered both anonymity and doormen. Finally, she would settle down to a place she called home.

In 1953 Garbo bought the fifth-floor apartment at 450 East Fifty-second Street. Built in 1927 and boasting a Venetian-Gothic façade, it was a site of considerable intrigue, even before Garbo moved in. During Prohibition it housed a private speakeasy called the Mayfair. Situated at the end of a rare Manhattan cul-de-sac, with an unobstructed vista up and down the East River, the building has long had a colorful array of residents. Henry and Clare Boothe Luce maintained a triplex. Noël Coward, Edgar Kaufman and Alexander Woollcott were also among the illustrious that have made it their home. Though officially called the Campanile, it was dubbed Wit's End by Dorothy Parker. Tickled by the legacy. Garbo moved in.

|

David Levine's The Pink Hat is one of the paintings in the living room. A friend of the artist's recalls Garbo at the opening in which the seascape was exhibited. “She came in, spotted the painting, bought it and left–five minutes later.”

|

DAVID HAYS / © GRAY REISFIELD

DAVID HAYS / © GRAY REISFIELD |

What she acquired echoed her inner aesthetic.

|

FRITZ VON DER SCHULENBURG / © GRAY REISFIELD

FRITZ VON DER SCHULENBURG / © GRAY REISFIELD |

Pierre Bonnard's Les Coquelicots hangs prominently in the living room. Elsewhere are portraits and a still life by Alexej von Jawlensky and oils by Georges Rouault and Juliette Juvin.

|

Collecting paintings, antiques and furnishings for her new residence became a lifelong, international pursuit. Whether on a “trot” about New York, a brisk walk through Paris or a cruise around the Mediterranean, Garbo loved the quest for her treasures. What she acquired echoed her inner aesthetic. Her apartment was a place of beauty, wit and color.

|

A panel painted after François Boucher adorns the upper part of a Louis XVI trumeau in the living room. The painted and parcel-gilt demilune commode below is Italian. At right are flower paintings, from top, by Georges d'Espagnat, Kees van Dongen and Louis Valtat.

|

DAVID HAYS / © GRAY REISFIELD

DAVID HAYS / © GRAY REISFIELD |

FRITZ VON DER SCHULENBURG / © GRAY REISFIELD

FRITZ VON DER SCHULENBURG / © GRAY REISFIELD |

Renoir's Enfant Assis en Robe Bleu (Portrait of Edmond Renoir, Jr.), which dates from 1889, hangs above a Régence parquetry commode in the living room. The circa 1835 Staffordshire equestrian figures stand alongside one of a pair of Han pottery vases mounted as lamps. The corner chair is Louis XV.

|

Robert Delaunay's Woman With Parasol was a cherished canvas. For Garbo, color was essential in art and décor, and she surrounded herself with vibrant hues. “I love color,” she once said. “With me it's inborn. I just know. I didn't have to learn it.”

|

DAVID HAYS / © GRAY REISFIELD

DAVID HAYS / © GRAY REISFIELD |

A friend of Garbo's who herself presides over one oft the world's greatest private art collections said it best: “She had a natural taste.” Although she was fond of discussing art and design with the experts and trendsetters of the day, Garbo had her own instincts. She never followed fashions, she created them. She had tremendous faith in her judgment and was very sure of her innate and diverse talents. “I never set out to be an actress,” she once remarked. “I would have been good at an number of things.”

Garbo created many colourful rugs for the apartment. The first series she called Birds in Flight, which chronicles a particular period in her aesthetic life. She began the series in 1962 with two rugs, one for her bedroom and one for what she called her “closet room,” which she had transformed from a small library. The designs are boldly geometric and charged with color. Each has a central medallion motif, and the forms, though abstract, are translatable to their winged inspiration. By 1966, when Garbo made the last rug in this series, the geometric shapes, which she had conceived and sketched, could certainly have been considered avant-garde. The series, though colourful and modern, never compromised her classical sensibilities.

For the halls, Garbo designed runners with a trellislike pattern. Except for the rugs, the long corridors were relatively unadorned, compared with the rest of the apartment. The flocked brown wallpaper there might have fooled a visitor into expecting musty high Victoriana. In contrast, the chartreuse and shocking-pink tones of her rugs were more suggestive of the gardenlike rooms beyond–her prelude, so to speak. It was all very schematic, though it did not appear to be contrived.

|

FRITZ VON DER SCHULENBURG / © GRAY REISFIELD

FRITZ VON DER SCHULENBURG / © GRAY REISFIELD |

Jean Atlan's Composition, a gift to the actress from her friend Elie de Rothschild, is set above a Continental Rococo painted chest of drawers in the master bedroom. The small gouache is Dimitri Bouchène's Costume Design for a Masked Lady.

|

The “closet room,” which Garbo created from a small library, is highlighted by one of the carpets she designed for her 1962 series, Birds in Flight. Over the closet is part of her array of hats; others are stacked on a carved and painted Russian provincial tea table from circa 1880. The mahogany dressing table is Louis XV. Garbo chose the upholstery and drapery fabric, by Fortuny. which features African tribal motifs.

|

BILLY CHUNNINGHAM / © GRAY REISFIELD

BILLY CHUNNINGHAM / © GRAY REISFIELD |

Composing the rugs was a wonderful outlet for Garbo's creativity. She was tireless, involved in every process. Ever practical, she would sit cross-legged on the floor when working on them. To her, it was the obvious perspective from which to design a rug. Roger McDonald, then a young man at V'Soske, the company that produced her designs, recalls his illustrious client: “We worked and we worked until we achieved what she wanted.” Now V'Soske's design director, McDonald still feels Garbo's influence, particularly with color. “She knew just how to use color to energize a space,” he says. “The rugs she designed held to the floor; they were never mincing, never overpowering.”

For her bedroom, Garbo disassembled an old Swedish skåp, a hung armoirelike piece she hand bought many years before at an auction in Stockholm. Typical of her taste in such furnishings, the floral carvings are natural and delicate. After she had the entire piece taken apart, she designed both a bed and a niche with the splendid panels.

|

RUTH HARRIET LOUISE /

RUTH HARRIET LOUISE /

COURTESY GRAY REISFIELD |

Garbo, in a circa 1929 photograph. Of her legendary desire for privacy, she remarked in a 1928 interview–one of the few she ever granted–“I wanted to be alone, even as a child. I used to go to a corner and think…. Thinking means so much, even to small children.”

|

For the bedroom and the “closet room,” she chose a Fortuny fabric with African tribal symbols set against a mottled salmon-colored background. Despite its primitive roots, the fabric is wonderfully modern.

Garbo was passionate about color. She would frequently proclaim, “Color makes a room sing.” Her rooms certainly did. She amassed a collection of hundreds of paintings and artifacts that resonated with color–and character. When she spied something in a shop or auction house that struck a chord, she would moan in her deep, wistful voice, “If only I had the room.” She learned to find places. In the living room, she hung a veritable chorus of paintings, stacked on the walls up to the ceiling. The bookcases and tables brimmed with whimsical porcelains. The effect was dazzling, like a garden in full bloom.

The apartment was resplendent with flowers, both real and re-created, since her collection was filled with floral motifs. There were delicately carved roses on an eighteenth-century marquise; painted tulips decorated a Rococo chest of drawers; the halls were flecked with light from floriated pastel-colored porcelains mounted on small chandeliers. Her art collection included dozens and dozens of splendid and lively floral still lifes by an assortment of artists: Pierre Bonnard, Kees van Dongen, Louis Valtat, Georges d'Espagnat, Alexej von Jawlensky, Madelaine Lemaire and even Garbo's own artist brother, Sven Gustafson. She was always finding a spot for seductive little anonymous painted bouquets she came across in her travels.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

“I never set out to be an actress,”

Garbo once remarked. “I would have been

good at a number of things.”

¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯

Her selections were not limited to floral subjects, though one might conclude that Garbo was drawn to images of innocence. The Renoir above the fireplace depicted a touching scene of a young nursemaid reading to a boy, the artist's youngest son. Next to it was a small, quiet canvas that might be Garbo herself, seen from behind, staring into a calm sea, wearing a trademark floppy hat.

The actress was credited by her art-collecting contemporaries with acquiring the work of the German Expressionist Jawlensky before it was widely sought after. Her paintings, now known as the Garbo Jawlenskys, were composed between 1915 and 1918. The period is recognized as a time of renewed energy, hope and harmony fort the artist. Garbo was fascinated by these paintings, particularly the thickly outlined faces, Jawlensky's portraits are dramatic and bold, color infusing them with a rich poignancy.

Garbo's largest painting, Robert Delaunay's Woman With Parasol, was also her favourite. Her eyes would linger over the canvas more than over any other. It featured the artist's wife, Sonia, strolling on a still-moist garden path, a sun shower of vibrant hues.

There were many truly exceptional works in Garbo's collection–paintings of flowers, clowns, children, funny little dogs and festive people. To her, each had its own story, its own life. Her art provided a colourful audience with which to enjoy the sweeping views from her apartment. And we did–especially at sunset, when the dancing light that reflected off the river below made the apartment a magical place. Shrouded in secrecy, she tended an oasis of color and imagination in the middle of Manhattan. This was Garbo's secret garden. |

|

from: Architectural Digest April 1992

© Copyright by Architectural Digest

|